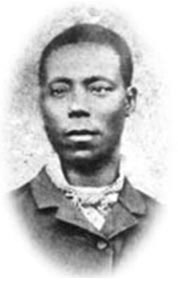

Paul Bogle and George William Gordon, both hanged after the Morant Bay Rebellion and now honoured as National Heroes of Jamaica. Images copied from the Jamaican Government website.

The Caribbean sugar industry suffered a crisis in the mid-nineteenth century. Taxes were abolished on foreign sugar, making it cheaper for British merchants to import from Cuba and Brazil (which continued to use slave labour) than from their own colonies. Sugar beet was also being grown successfully in Europe, adding to the competition. Jamaica was among the hardest hit by the crisis as the productive land was almost exclusively given over to sugar cane. This led to economic depression and civil unrest.

In 1848 the House of Commons appointed a select committee to investigate the conditions and prospects of sugar and coffee planting in Britain's possessions in the East and West Indies and Mauritius, and to consider what measures could be adopted to relieve the hardship then being suffered.

Among those who gave evidence was Jamaican plantation owner Alexander Geddes. He was questioned on 13 March 1848. The following extract is from the minutes of his testimony in which he responds to a question about the possible consequence of the continuing fall in revenue on the island.

I have stated most emphatically that the islands revenue is in the course of disappearing, and will in the absence of some remedial measure disappear in two or three years; for as the cultivation decays the consumption of all articles on which the revenue is raised will become limited. In that case the clergy will remain unpaid, and the church doors will of course become shut; the judges and other high functionaries will remain unpaid, and of course the courts of justice will be shut; there will be no means of supporting prisoners in the gaols or penitentiaries, and the doors of those institutions must be thrown open; the patients in the public hospitals will be left to their fate entirely; the police must be disbanded, and society will become disorganized. If your Lordship will allow me, I will just glance at the geographical position of Jamaica in reference to other countries. It has, 90 miles to the westward of it, the great island of St Domingo, now in a state verging on barbarism; 80 miles to the north is the still larger island of Cuba; four days' sail from Jamaica is the island of Porto Rico. Twice within the last 50 years have the more civilized portions of the inhabitants of St Domingo had to flee to Jamaica for refuge. Looking to the extent to which savage Africans are introduced into Cuba, and that they are kept in a state against which nature must ever rebel, it is to my mind but a question of time when civilization must disappear by an insurrection in that country; the same may not take place in Porto Rico, because there there is a greater proportion of free inhabitants. Eighteen months ago Jamaica presented as fair a chance as the most ardent friend of freedom could desire, of every hope which was ever cherished of the results of emancipation being accomplished. On the repeated assurances of the various organs of the Government here, from the time of Lord Nomanby downwards, that a preference would be ever given to us in the home market, our institutions, clerical, civil, judicial, correctional and sanitary were placed upon a footing of the greatest efficiency. A penitentiary and a lunatic asylum upon the most approved plans are now in the course o f erection. If the revenue disappears, as it will in the absence of remedial measures, those institutions will disappear also. Government may maintain a garrison there, and it may maintain those institutions, but civilization cannot advance, because the avenues to advancement will be shut in the total decay of commerce and agriculture. If the light of civilization is extinguished in Jamaica, and it appears likely to be so, the chances are that in the next 30 to 40 years the greatest islands in that archipelago will present precisely the same picture that St Domingo does, of men reverting rapidly into barbarism. The islands will become the resort, as they have been within my recollection, of buccaneers and pirates, and they will be totally lost to the civilized world. The cause of African freedom, at present seriously injured by what has taken place in our colonies, will be thrown back to an indefinite period.

This account of Geddes' evidence is taken from Bath Library Service's original edition of the select committee's fourth report. You can read further testimony from the report in the sections on The 1848 Select Committee and Slavery in Brazil.

Although Jamaica did not descend into the anarchy Geddes predicted, conditions remained difficult and were made worse by successive years of drought. On 11 October 1865 Paul Bogle, a Jamaican Baptist minister working on behalf of the impoverished local community, led a group of villagers from Stony Gut to the court house at Morant Bay to protest about the arrest of a local man following several months of discontent. Bogle had earlier written to the Colonial Office describing the desperate state of affairs on the island. The letter was shown to Jamaica's Governor, Edward Eyre, who denied there were any problems.

Violence broke out at the Morant Bay rally and the town briefly came under control of Bogle and his followers. The British retaliation was fierce. Martial law was imposed, hundreds of black people were killed and thousands of black homes were burnt. Bogle was eventually captured and hanged. The short-lived rebellion prompted fierce debate in Britain about conditions in the colonies and two unsuccessful attempts to bring Eyre to court to face charges of murder. Those who supported Eyre included Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin; those against him included John Stuart Mill and Charles Darwin. Today Bogle and George William Gordon, who was also hanged by the British authorities in the wake of the rebellion, are national heroes in Jamaica.

|

|

The following extracts are from British letters and articles sparked by the Morant Bay events:

I highly applaud the course which your [Anti-Slavery] Society has taken on the horrors committed in Jamaica, and if I were in England I should attend the meeting on Tuesday.

There is little danger that a Government, containing such men as some of the present ministers, will defend or uphold the savage deeds which have been perpetrated, or absolutely screen the perpetrators. But there is always danger from human weakness, there is danger lest the sympathies of a Government, with its agents, should enable the guilty to get off with mere disavowal and rebuke, or some almost nominal punishment. I earnestly hope that the nation will not allow justice to be thus trifled with, but will insist on a solemn judicial trial of the Governor of Jamaica, and of all under his orders who have been guilty of hanging or flogging alleged rebels without trial.

The commander of one of Her Majesty's ships, if his ship is lost, though no one accuse, though no one even suspect him of being to blame, must, by an inexorable rule, be tried by court-martial, as if he were the guiltiest of men, that a competent judicial authority may determine whether he has committed any offence. And shall the authors of deeds which scarcely any conceivable excuse that could be made for them would prevent from being a lasting disgrace to the country, not be subjected to a similar ordeal?

To those who object that men ought not to be judged without a hearing, I answer, that we do not judge them; we demand that they should be judged. John Stuart Mill, 1865

Truly one knows not whether less to venerate the Majesty's Ministers, who, instead of rewarding their Governor Eyre, throw him out the window to a small loud group, small as now appears, and nothing but a group or knot of rabid Nigger-Philanthropists, barking furiously in the gutter. Thomas Carlyle, 1867

... unless I am misinformed, English law does not permit good persons, as such, to strangle bad persons, as such. On the contrary, I understand that, if the most virtuous of Britons, let his place and authority be what they may, seize and hang up the greatest scoundrel in Her Majesty's dominions simply because he is an evil and troublesome person, an English court of justice will certainly find that virtuous person guilty of murder. Nor will the verdict be affected by any evidence that the defendant acted from the best of motives, and, on the whole, did the State a service.

Unless the Royal Commissioners have greatly erred, therefore, the killing of Mr Gordon can only be defended on the ground that he was a bad and troublesome man; in short, that although he might not be guilty, it served him right.

I entertain so deeply-rooted an objection to this method of killing people-the act itself appears to me to be so frightful a precedent, that I desire to see it stigmatised by the highest authority as a crime. T H Huxley, 1868

W F Finlason's book The History of the Jamaica Case: being an account, founded upon official documents, of the rebellion of the negroes in Jamaica was published in 1869. The author was entirely supportive of Governor Eyre's conduct in the Morant Bay events. In the book Finlason quotes from Archibald Alison's History of Europe on the dangers to white people of black rebellion, which Finlason describes as being 'necessarily, sooner or later, a war of extermination'.

The insurrection of slaves is the most dreadful of all commotions. The West India negroes exterminate by fire and sword the property and lives of their masters. Universally the strength of the reaction is proportioned to the oppression of the weight which is thrown off. Fear is the chief source of cruelty. Men massacre others because they are apprehensive of death themselves. Revolutions are comparatively bloodless when the influential classes guide the movements of the people, and sedulously abstain from exciting their passions. They are the most terrible of all contests when property is arranged on one side and numbers on the other. The slaves of St Domingo exceed the atrocities of the Parisian populace.

The 'slaves of St Domingo' referred to here had organised a successful black independence campaign that had led to the defeat of the French in 1804. Echoing the concerns of Geddes in his testimony to the select committee referred to above, Finlason twice points out in the space of a page that St Domingo is only 'one day's sail' from Jamaica and that the island 'has ever since been a standing temptation to the blacks in Jamaica, and a standing terror to the whites'. He later quotes approvingly another passage from Alison on the 'disastrous results' of the emancipation of Jamaica's slaves.

Generally speaking, the incipient civilisation of the negro has been arrested by his emancipation. With the cessation of forced labour, the tastes and habits which spring from and compensate it have disappeared, and savage habits and pleasures have resumed their ascendancy over the sable race. The attempts to instruct and civilise them have, for the most part, proved a failure; and the emancipated African, dispersed in the woods, or in cabins erected amidst the ruined plantations, are fast relapsing into the state in which their ancestors were when they were torn from their native seats by the rapacity of Christian avarice. The savage was made free without his having gained the faculty of self-direction; hence the failure of the whole measure, and the unutterable misery with which it has been attended. In 1838 the Government was compelled to venture on the hazardous step of total freedom, which has completed the ruin of the West Indies.

Finlason also quotes from an address made at Morant Bay on 29 July 1865 by George William Gordon, which he describes as 'inflammatory', believing it contributed to the unrest that led to the October rebellion. Gordon was the son of a white planter and black slave who was elected to the Jamaican House of Assembly as an advocate for the island's destitute black people. In his address, entitled 'State of the Island', he said:

Poor people of St Ann's! Starving people of St Ann's! Naked people, & c. You who have no sugar estates to work on, nor can find other employment, we call on you to come forth. Even if you be naked, come forth and protest against the unjust representations made against you by Mr Governor Eyre and his band of custodies. You don't require custodies to tell your woes; but you want men free of Government influence - you want honest men.

These extracts from Finlason were taken from the copy of his book held by Bath Central Library. There is a digital version available on the University of Michigan's Digital General Collection website.

R W Kostal's 2005 monograph A Jurisprudence of Power: Victorian Empire and the rule of law focuses on the significant impact the Morant Bay events had upon English political law. A PDF of the monograph can be downloaded on the Oxford University Press website. |